News & Features

Awards

Best Documentary Short, Los Angeles Women's International Film Festival for Escape, 2012 Winner, 5th Annual International Women and Minorities in Media Fest for Escape, 2012

Official Selection, United Nations Association Film Festival, for Escape, 2012

Honorable Mention, Photo Book Now, 2009

Special Prize by Juries, Day's Japan, for Escape, 2008

Juror's Choice, Santa Fe CENTER Project Competition for Escape, 2008 Media

NYC Covid Lockdown

Director

Visualizing Racism

Photos and Text by Marvi Lacar for the Washington Post

If the pain of overt racism is like a brutal stab wound — instant and searing — the trauma of systemic and casual racism is like the phantom pains from an amputated limb. It is the constant pinpricks of a wound that can’t fully heal. It is the external reminder that you’re not quite like the others, and the gnawing self-doubt that you may never be enough.

But to speak of this type of pain can be risky. You can be told, “You have such a chip on your shoulder. Get over it!” or “You’re always acting like a victim!”

Most people of color play a balancing act when advocating for ourselves and our children. We straddle the line between finding a space to speak openly about injustice and trauma, and guarding ourselves so that our experiences and our grief aren’t turned into racial tropes. We proceed with caution, lest our stories be stripped of empathy and subsequently used against us. There are consequences of vulnerability.

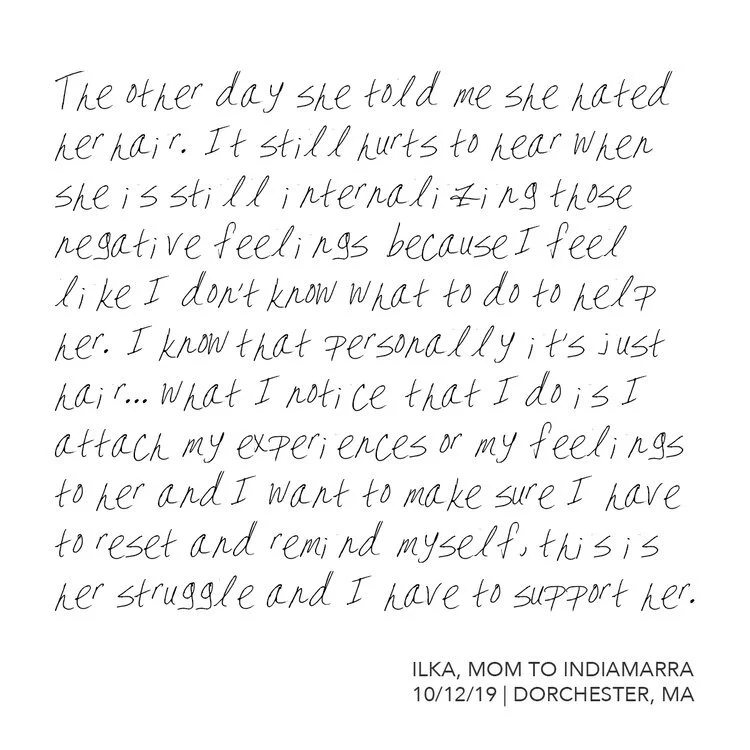

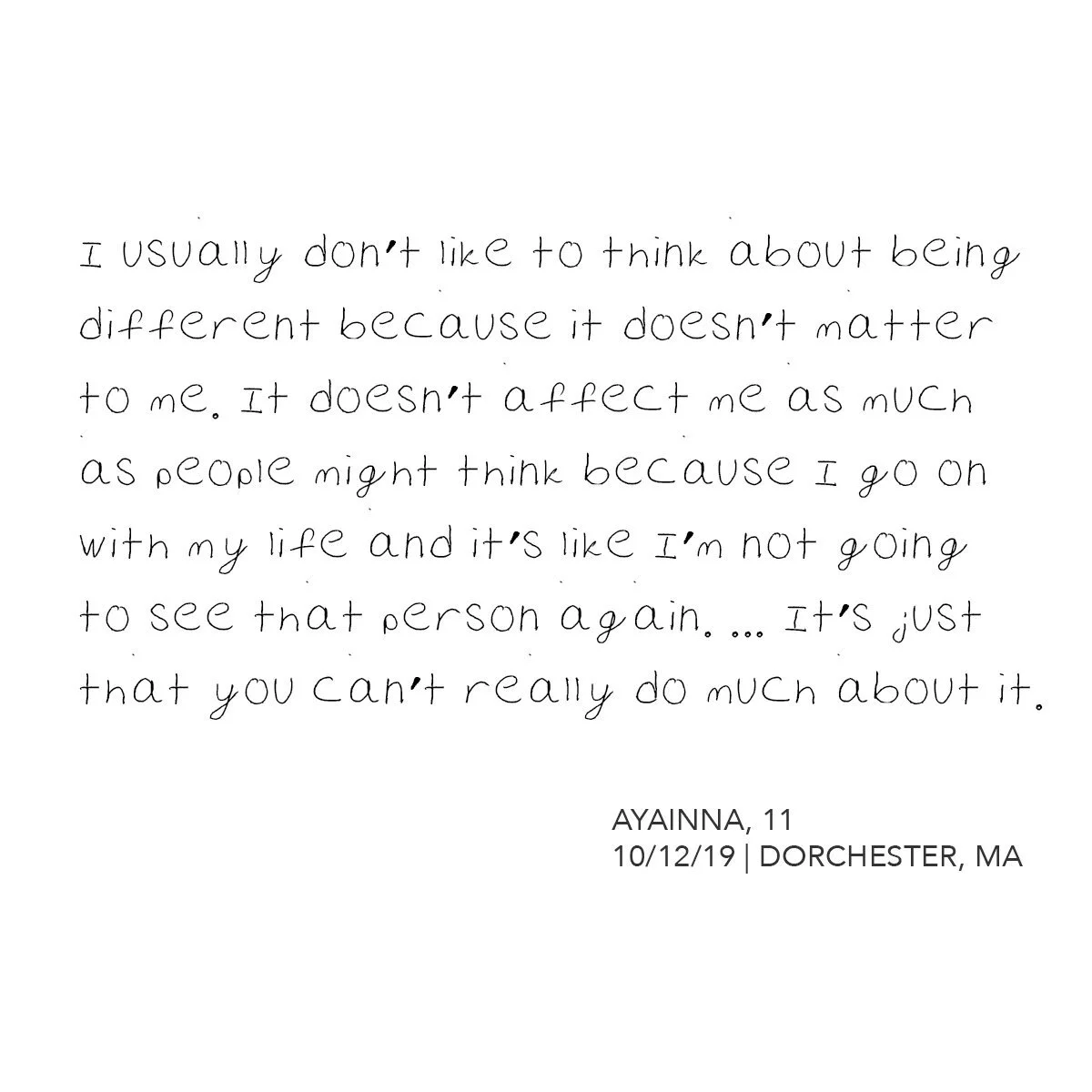

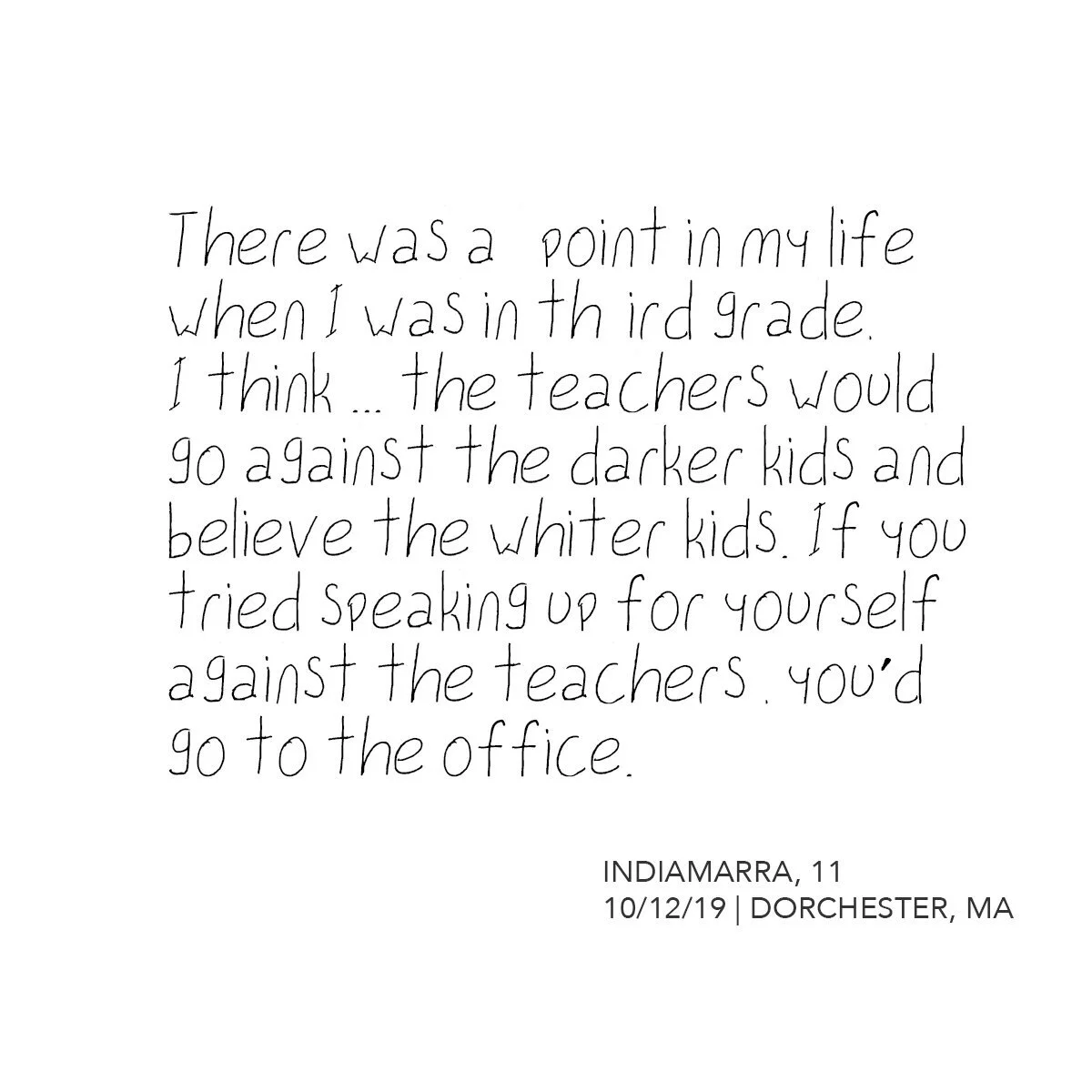

Yet some parents, like Ilka Alcantara and Alicia Volel, are cognizant of their inherited trauma and are more open to addressing the reverberations of hate around their two girls. Best friends Indiamara and Ayainna, both 11, grew up in middle-class homes in Dorchester, Mass., with two working professional parents. What is grim about their stories is the commonality of their experiences. They speak of everyday realities many children and families of color have grown inured to — realities so typical, in fact, that these daily offenses no longer possess an urgency in their hierarchy of problems.

Escaping Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage

Director, Photographer

For the Maasai tribe of Kenya, female circumcision (currently refered to by law as Female Genital Mutilation or FGM) is considered a rite of passage. It is a prerequisite to marriage as it is believed to turn a girl into a woman and cleanse her blood, which will finally make her worthy of a man’s touch. It is also believed to stifle her libido thus ensuring her fidelity to her husband. Girls undergo this rite from as early as 8 to 15 years of age.

Immediately following circumcision is marriage, which brings in a significant amount of livestock and cash flow to the girl's family. For a poor pastoral family, a girl’s dowry will mean a rise in status in their community because property commands respect. Property however, is not limited to inanimate objects. Girls and women are considered property. They can be exchanged, married off or banished at the will of the husband, father, brothers or even uncles. The man is the final decision-maker and to contradict him would be an unfathomable act of disrespect. A girl cannot scream or cry when her clitoris and labia minora are cut off for she is not to disobey the will of her father. Once she is married, she can no longer proceed in her studies as she is to tend to her obligations as a wife. She is to cook, clean, and procreate.